Growth

Aug 15

How To Run A Growth Experiment

You’ll never meet a marketer who says they don’t want to be ‘data-driven’. Likewise, the concept of experimentation—rapidly testing an idea with strict expectations of success and failure—has overtaken the Don Draper days of marketing campaigns and creative ideas. Revenue leaders will usually prefer a growth team over a marketing department, but that’s easier said than done.

Growth experimentation is crucial for the modern marketer, but its success is often much more dependent on the methodology used than the experiment itself. A solid growth experiment doesn’t just drive success for the company, it also makes it much easier for new hires to understand what has been done in the past. A true ‘growth lab’ will show a track record for everything that has been done at the company, and make building on those successes much easier.

In this article, we will break down the steps needed to run a successful growth experiment using the experiment we recently ran at Divisional as an example. This will help you not only understand the theoretical aspects of designing a growth experiment, but will also demonstrate how to implement those steps in real-life scenarios.

Product Marketing: What are you testing?

A common misconception is that growth experiments always involve testing channels. This can be true, but more often, it involves testing a specific assumption within a channel. For example, many startups (ourselves included) want to test outbound email. We can assume:

“Startups with Seed funding but no marketer support have the greatest need for fractional growth help”

If we shortlist 100 startups and reach out to them via email, it’s possible that 0 will respond positively. That doesn’t mean that outbound email is a bad channel, just that our assumption is invalid, and/or our assumption is invalid via outbound email. Failing to note the difference leads to startups quickly invalidating fruitful channels, which can stunt your growth significantly.

The basis of growth experimentation comes from a strong understanding of the product and customer. Every channel can fail for your company, if it’s approached with the wrong target audience and/or messaging.

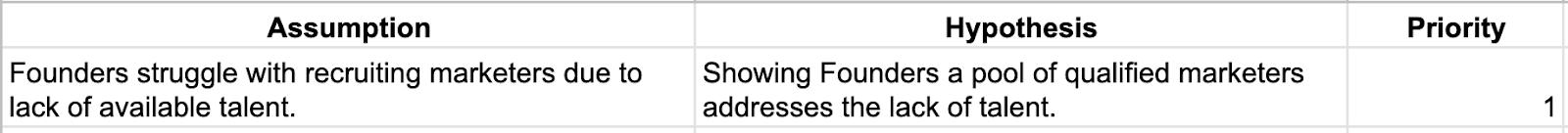

Before creating a growth experiment, start by outlining all your assumptions and hypotheses about your customers. These can be fairly widespread, where the assumption is about how you believe your target customer acts or thinks, and the hypothesis is how your product addresses this. Some combinations will be stronger than others, so you should prioritize them accordingly.

If you skip this step, then it becomes exponentially harder to identify the reason behind the success (or failure) of a given experiment. The earlier you start building assumptions, the better, as it can also be helpful to reflect on them to see how your thinking has evolved. Founders rarely see their product/customers the same ~ 5 years after starting, and marketers are no different.

How to create a growth experiment

Once you know which assumptions you’re testing, you can move to thinking about the channels behind the test. From the example above, if the assumption is that founders struggle with recruiting marketers due to lack of available talent, and your hypothesis is that showing them a pool of qualified marketers would solve that issue, you can start to ask yourself several questions:

- Where do the founders I’m targeting exist?

- Where would they be most receptive to recruiting material?

- What has worked in the past for us to get in front of founders?

Although these questions are specific to the hypothetical example we outlined, you can make them more generic and widely applicable to any growth experiment. Here's some guidelines to help you get started:

- Where do the [target personas] hang out/spend their time?

- What channels do they typically visit to consume [topic]-related information?

- Which platforms have worked well for us in the past when trying to get in front of [target personas]?

- How much of a lift is it to run an experiment on this channel? Do we have the resources to pull that off?

Choosing the channel

You might assume that founders are most often on LinkedIn when recruiting, and it’s also the easiest place to create a target audience (either custom upload or companies/job titles).

The other thing to consider is how hard it is to launch the experiment (’the lift’). It might be easier for you to build copy and creative for LinkedIn Ads than to scrape a target list and build a copy for outbound email. Therefore, you might prioritize LinkedIn Ads as the channel to reach founders for this experiment.

If it’s helpful, you can also list out alternative channels and reflect on your rationale. This can be useful in the future if you’re looking to test new mediums, or combine them with the one that you end up choosing.

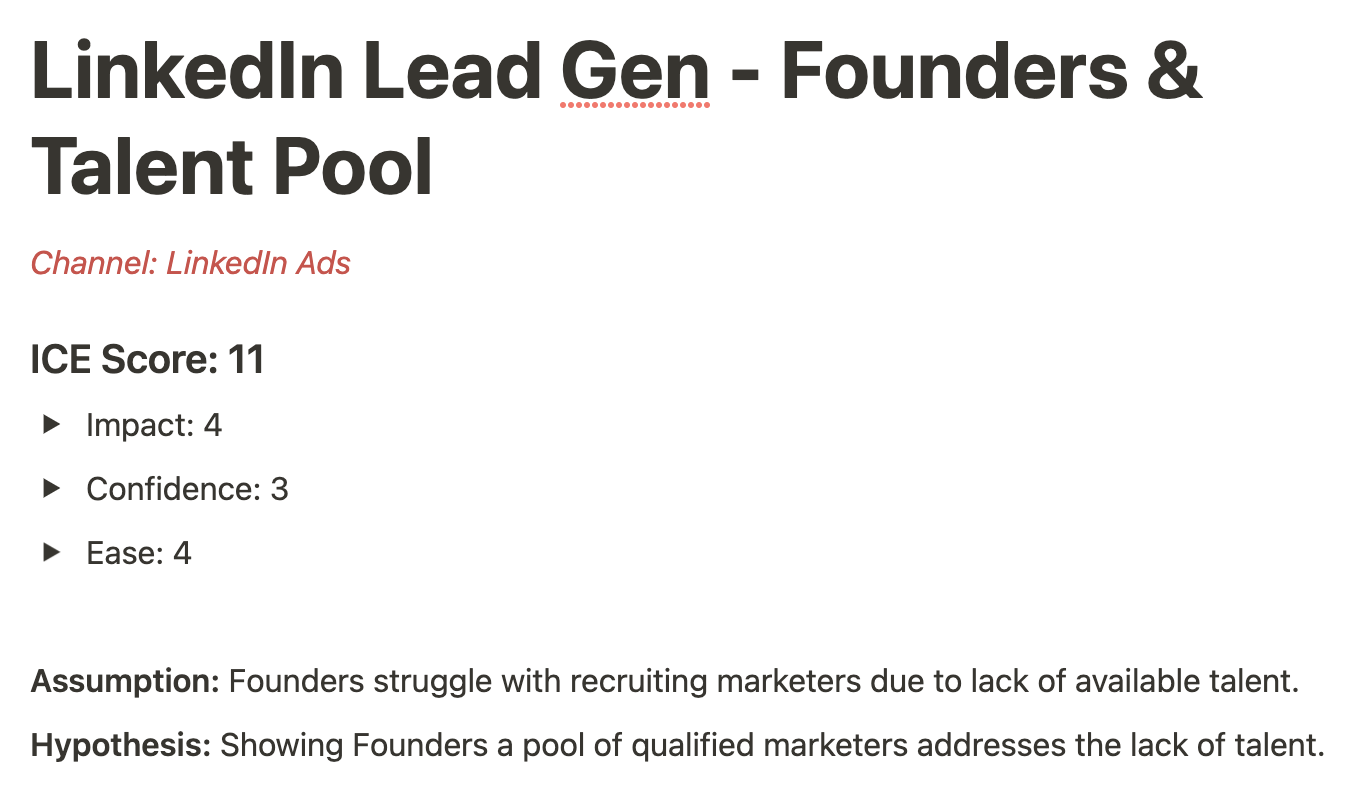

Before you explore a particular experiment, you can benefit from putting your rationale through a test called the ICE Score. It stands for Impact, Confidence, and Ease. The ICE Score forces you to evaluate the tradeoff between how much growth the experiment will drive (impact), how sure you are that it’ll work (confidence), and how many resources it’ll take to get the experiment live (ease).

Creating parameters

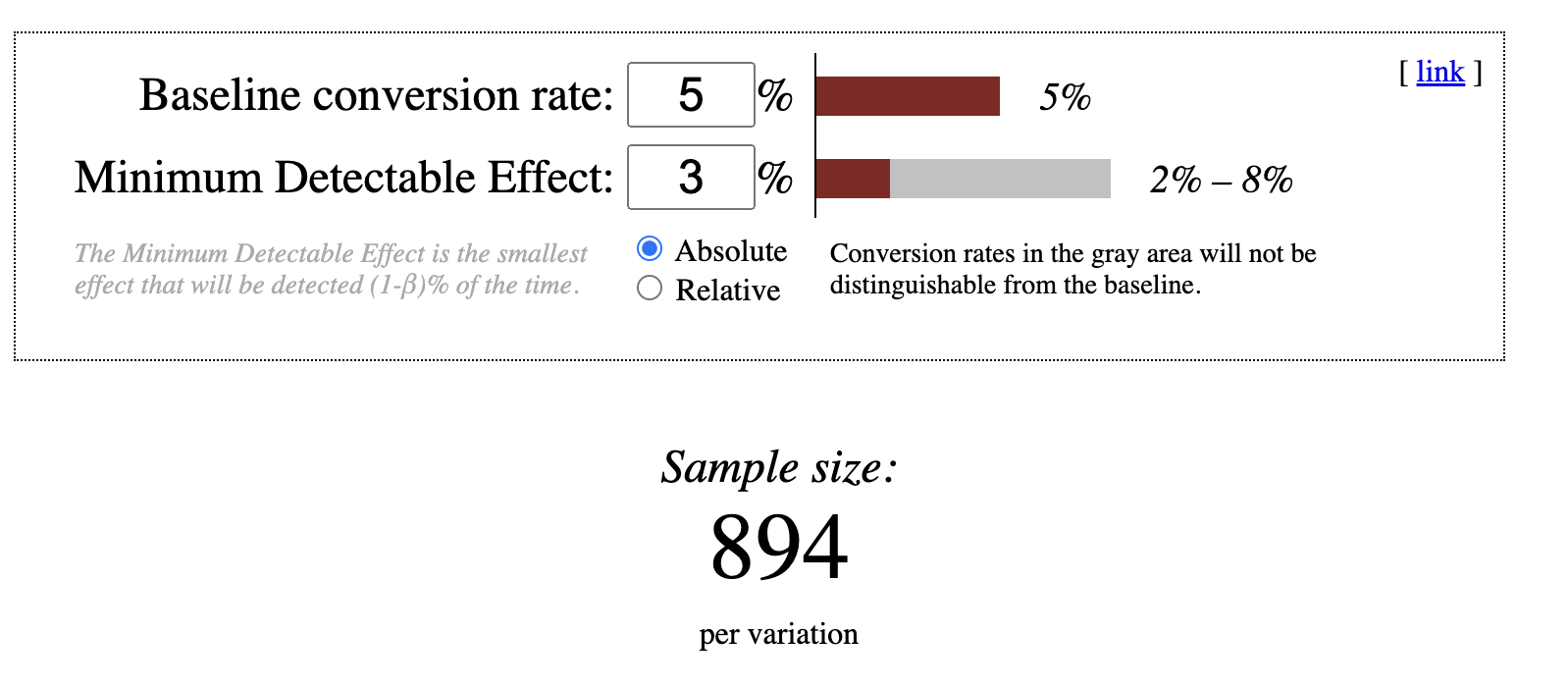

With a channel in mind, you can then start creating parameters around your experiment. This will include the expected results and milestones along the way. Statistical significance (stat sig) is an important concept in experimentation, and will inform how you think about your experiment’s expected results.

Stat sig means that your test has sufficient data to be deemed a valid test. For example, if you get 1,000 new users a week, a test that is run on 10 users is likely to be deemed statistically insignificant. Not all experiments need to be stat sig, but determining the goal beforehand improves the integrity of your experiment.

A directional experiment is one that will never reach stat sig, but will give you confidence whether your assumption was correct. For early stage startups, where budgets are tight and there isn’t enough data to get statistically significant results, directional experiments are commonplace. This goes double for startups who are experimenting on their customers (i.e. not with net new audiences), such as Conversion Rate Optimization (CRO) on the website or product. If you are only getting 50 visits a day, then testing a landing page and expecting stat sig will be near impossible.

In contrast, a conclusive experiment is one that is dependent on reaching stat sig. You must make this distinction early on and BEFORE starting your experiment, otherwise you will jeopardize the validity of the results.

Finally, you should decide on milestones to accompany your expected results. This tells you when to check on your experiment and when to make a decision based on the initial results.

See below for an experiment template that includes the parameters discussed above:

Sample growth experiment

Let’s take the example above to create an actual growth experiment, using the template. For starters, we’ll begin with the assumption and hypothesis:

- Assumption: Founders struggle with hiring marketers because the quality of talent isn’t high enough.

- Hypothesis: Presenting founders with a pool of qualified marketers will increase the likelihood that they engage.

Next, we’ll work on prioritizing channels based on the combination that we are testing:

- LinkedIn Ads: Easiest to reach our target audience via custom upload or job title targeting.

- Outbound Email: Lowest cost, but likely that founders are inundated with sales emails, therefore won’t respond.

- Paid Search: Founders are likely not using Search when looking for qualified marketers.

- Other Paid Social: Diverse channels (i.e. Google Display) will yield a lower Cost Per Click (CPC) to reaching Founders, but have much lower intent in their recruiting journey.

- Influencer: Founders would have higher affinity with a recruiting influencer but it would take a larger lift to test (i.e. need a stronger value prop) to incentivize the influencer. Good idea for a follow-on campaign.

With LinkedIn Ads as our chosen channel, we’ll move on to creating the growth experiment:

Rationale: CPC of ~ $9 to target a founder audience (see below), budget of $900. Daily budget of $100 would yield results in 9 days. If typical lead gen conversion rate is 5%, and we’re assuming a 3% variance (2% to 8% CR), then we’d need 894 clicks for stat sig. Given that this is our first experiment, we will make this a directional instead of a conclusive test.

Use this tool to determine the statistical significance of your experiment.

Expected results: Anticipating 100 clicks and 7 qualified conversions (7% CR) for a Cost Per Qualified Lead (CPQL) or ~ $129.

Milestones: The following will tell us, at a budget of $90 per day, how the experiment is going:

- In 2 days ($180 spent, 20 clicks), clickthrough rate (CTR) should be > 0.5%

- If > 0.5%, do nothing

- If 0.3% to 0.5%, pause lowest performing ads

- If <0.3%, begin developing new ad creative/messaging to test

- After 5 days ($450 spent), we should have 2-3 conversions (5% CR)

- If ≥ 2-3 conversions, do nothing

- If 1 conversion AND CPC is higher than $9, increase budget by 20% ($108 per day)

- If 1 conversion and CPC is ≤ $9, do nothing

- If no conversions and CPC is ≤ $9, pause campaign

- If no conversions and CPC is higher than $9, let campaign run to 50 clicks

By setting these milestones, we’re avoiding the following problems:

- We wasted budget by running an experiment that was far off from being successful

- Milestone: Budget vs # of Conversions

- We had incorrect inputs (i.e. proper messaging/creative) that would harm whether the channel is effective

- Milestone: Budget vs Clickthrough Rate on ads

- We didn’t budget enough for the experiment to gather enough data in the given time frame

- Milestone: Budget vs Cost Per Click

Creating growth sprints

An effective growth team will operate using growth sprints, where you prioritize experiments from your backlog every week, and choose what your team will be tackling. This ensures that your organization is continuously running experiments and iterating based on their success or failure. It is unlikely, with this method, that you or future hires will ever try the same thing twice.

The goal is to be constantly experimenting and ensure this culture is embedded in all aspects of your organization. Even at organizations that are at more advanced stages of growth, this activity can encourage creativity and critical thinking about the business, even when activities seem to be longer term and more predictable.

Conclusion

Growth experimentation is an exciting concept but difficult to execute upon if you don’t have the right framework or process. Start with a strong foundation via product marketing, and clearly outline your assumptions and hypotheses for an experiment. Next, choose and rank your channels for testing, and build an experiment using our sample brief. Once you launch the experiment, keep an eye on the milestones you set and ensure you’re running Growth Sprints to manage your experimentation backlog and iterate based on results.

Sounds like a lot to handle by yourself? Divisional can help—get in touch below and we’ll help you navigate your growth goals by connecting you to the people you need to achieve them.